MEDICAL AND CULTURAL CONSIDERATIONS OF FEMALE GENITAL CUTTING

By Maryam Fatima and Bunmi Afolabi

It is easy to condemn the practice of FGM/C as barbaric, based on the graphic images and stories that are shared that depict the physical, psychological, and emotional harm that is experienced by young girls and women who have gone through this procedure. The practice has severe physical, psychological, and social implications for young women and girls around the world. However, it is crucial to understand that the practice of FGM/C is enmeshed in and sustained through multilayered socio-cultural beliefs that exist in those communities.

What is FGM/C?

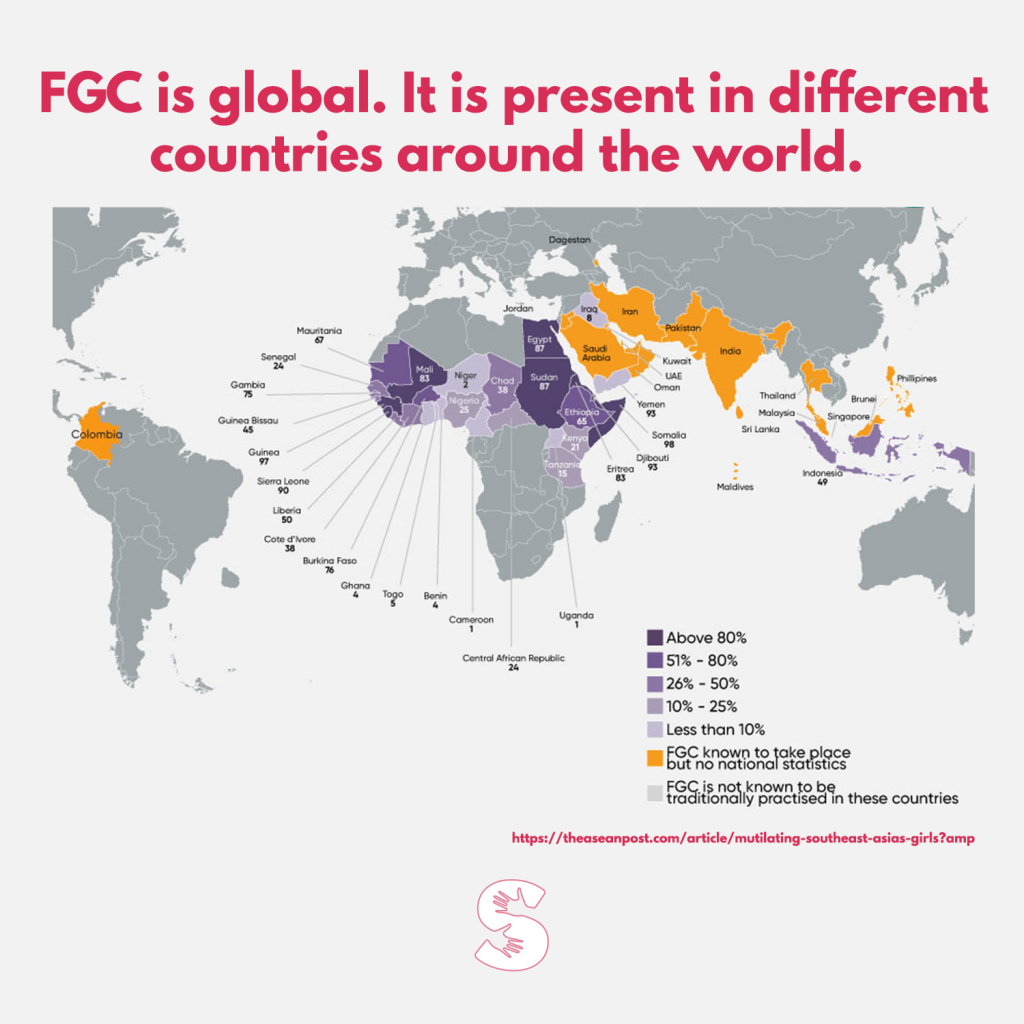

Female genital mutilation/cutting(FGC), also known as female genital mutilation (FGM), is a harmful practice involving the intentional excision of the female genitalia through cutting or burning.1 FGM/C is known to be performed all over the world but is mostly concentrated in northern and central Africa, the southern Sahara, parts of the Middle East and Asia.2

No one term fully captures the intent of the practice. The well known term FGM has a negative connotation, which implies that the practitioners intentionally seek to cause bodily harm to the young girl on whom the procedure is being performed. This also shows the use of problematic language by the Global West in talking about cultures in the Global South, particularly African cultures and tradition. Using the term “cutting” removes the stigmatization associated with practice, it allows actors/organizations to accomplish more than the others because it is less judgmental and value-laden. As a result, the term is more effective for engaging groups in dialog around this practice, and eventually bringing about its end.

Why is FCG a violation of human rights?

FGM/C is a violation of human rights as it constitutes extreme discrimination against women and girls.3 FGM/C constitutes gender specific discrmination because it involves the suppression of women as the practice has no medical benefits and instead causes harm and pain. Despite severe physical, mental and emotional health implications, FGM/C is still practiced in many communities worldwide, reinforcing harmful norms that perpetuate the idea that women’s bodies are subject to objectification stripping them of their value. FGM/C actively violates human rights as it is a breach of the convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, infringing upon consent and autonomy of women.

The 4 main types of Female Genital Cutting include:3

- Type 1: this is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans (the external and visible part of the clitoris, which is a sensitive part of the female genitals).

- Type 2: this is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans and the labia minora (the inner folds of the vulva), with or without removal of the labia majora (the outer folds of skin of the vulva).

- Type 3: Also known as infibulation, this is the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal.

- Type 4: This includes all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, e.g. pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing the genital area

Prevalence of FGM/C

- Approximately between 100 and 140 million women and girls have undergone this practice4

- FGM/C is performed in over 30 countries across the world5

- Around 90% of women have undergone FGM/C in Sudan, Mali, Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Somalia and Eritrea5

- Approximately 6,000 girls are circumcised every day6

Implications of FGM/C

Implications of FGM/C are not limited to, but inclusive of:

Poor Psychological Health7

- Induced by Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Phobia, Depression and Sexual Disorders

- Gynecological Health Implications8

- Menstrual difficulties

- Urinary symptoms

- Infertility

- Immediate Complications9

- Hemorrhage from the dorsal artery

- Shock and then infection,

- Urinary retention and tetanus, which can lead to mortality

Why is FGM/C Practiced

There are an array of factors that are associated with the practice of FGM/C that are mainly rooted in culture, tradition and religious beliefs. Most strikingly, FGM/C serves as an avenue to encourage patriarchal structures in societies and communities with the aim of guaranteeing moral behaviour and faithfulness of women to their husbands.10 Essentially, female children are cut to limit their excessive sexuality. FGM/C is justified in tradition in many ways, one of which is the sociological aspect that presents FGM/C as a transition into womanhood and more specifically as a rite of passage.11 Another significant justification of FGM/C is in relation to marriage, where FGM/C is expected to fulfil the virtues of morality, virginity and sexual control.11 The influence of marriage cannot be underestimated, especially in developing nations where it is not merely an option for women but instead is mandatory for survival as it ensures economic security and social status.11 As a result, virginity must not be comprised for women and FGM/C is wrongly believed to ensure it.

Socio-cultural symbolism of FGM/C

The negative perception of African culture stems from Western ethnocentric ideas that define what cultural practice is civilized and what is not. This narrative continues to be widely perpetuated in various fields, such as Academia, Medicine, Media, and Literature. FGM/C particularly, has been called barbaric and crippling (‘always torture’).12 The opposite can be said for the language associated with male circumcision or “say mutilation”.

- Male circumcision involves the partial or complete removal of the foreskin (prepuce); a number of methods are used. It is a sacred act in many religious faiths, such as Judaism, Islam, Christianity.13

However, Christianity is intertwined with Western ideals of civilization, that the practice of male circumcision has become so entrenched in Western culture. Parents who are not of Judeo-Christian or Islamic faith, give consent to health professionals to perform the cosmetic procedure. Ironically, we do not use the term mutilation when talking about male circumcision, we do not label it as a barbaric act, or call the practitioners of male circumcision monsters.

Esho uses the phrase socio-cultural-symbolic nexus to emphasize that the practice of FGM/C depends on the interpretations of bodily practices in different cultural contexts.14 Across the many cultures who practice FGM/C, the reasons vary as to why it is carried out and the age of those on whom it is conducted.

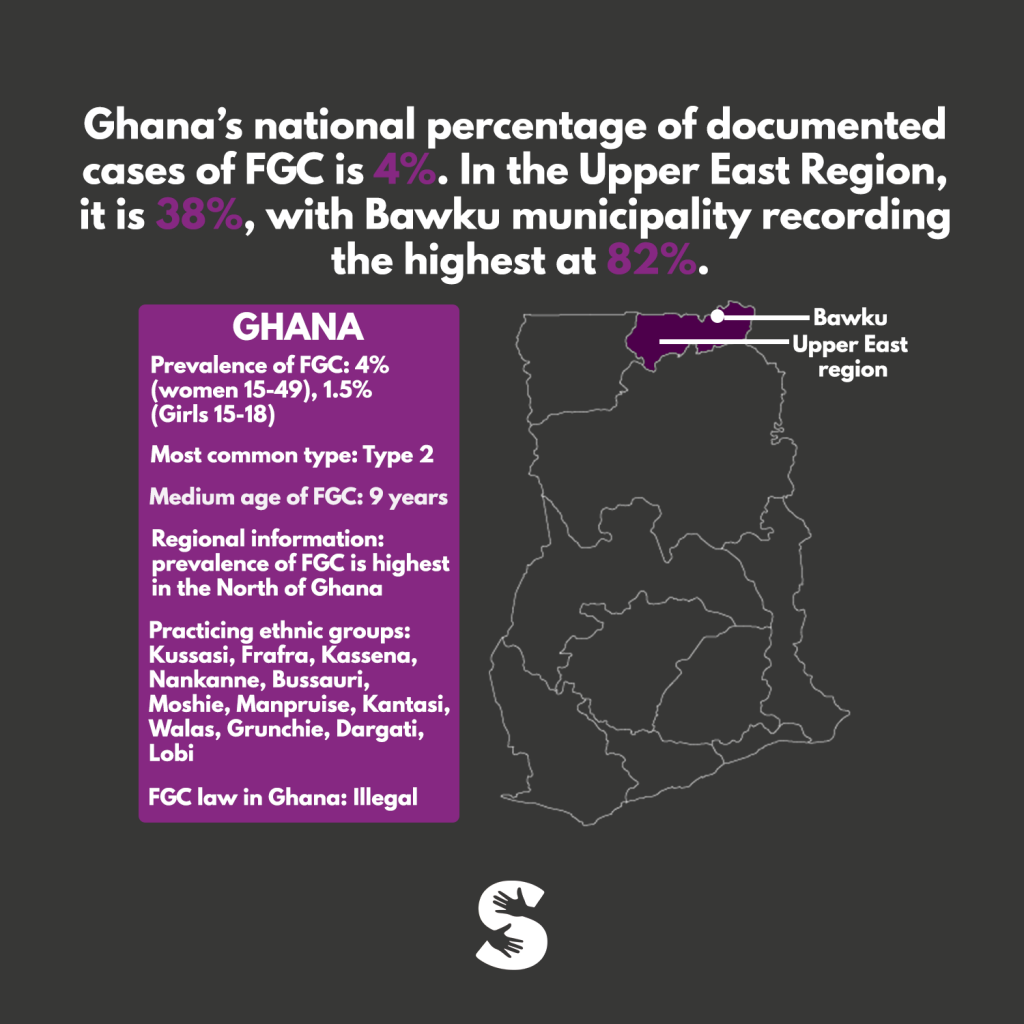

- Ghana’s national percentage of documented cases of FGM/C is 4%.15

- In the Upper East Region it is 38%, with Bawku municipality recording the highest at 82%” (Sakeah et al, 2018).15

- In 1989, former President Rawlings, issued a formal declaration against FGM/C and other harmful traditional practices.16

- In 1994, Parliament amended the Criminal Code of 1960 to include the offense of FGM/FGC. This Act inserted Section 69A that states:16

- “(1) Whoever excises, infibulates or otherwise mutilates the whole or any part of the labia minora, labia majora and the clitoris of another person commits an offense and shall be guilty of a second degree felony and liable on conviction to imprisonment of not less than three years.16

- For the purposes of this section ‘excise’ means to remove the prepuce, the clitoris and all or part of the labia minora; ‘infibulate’ includes excision (Type II) and the additional removal of the labia majora.16

Although FGM/C is banned In Ghana, it is typically seen as a rite of passage for young girls into womanhood. The completion of the procedure separates young girls from women and elevates the social status of those who have gone through the rite. In some communities where FGC is practiced, community members will not eat food cooked by a woman who is not cut, will not accept water from her, will not even sit with her. She will have difficulty getting married. An uncut woman is often viewed as unclean and therefore unable to participate fully in the community. With these social pressures, if a family chooses not to cut their daughter, they have risked severely damaging her social status. In this context, FGM/C is viewed as a central entity that defines female identity and acceptance into society. By undergoing the procedure, young women and girls acquire social power that enables them to participate in both private and public domains of their community.

The virginity myth, is another ideology that fuels the practice of FGM/C. In some communities where there is socioeconomic inequality and poverty is widespread, marriage becomes a means of escaping a life of constant lack. In such cases, virginity becomes a highly precious commodity. Young girls are taught that they need to preserve their virginity to be considered as a viable option for wealthy suitors. They see it as an obligation to preserve their virginity, to attain financial and economic security for herself and her family. As they give up their bodily freedom, they achieve partial social freedom. Young girls and women who do not undergo this procedure or who engage in premarital sex are effectively isolated from economic opportunities (through marriage). They are labeled as:

- promiscuous

- undesirable for marriage

- sexual deviants and,

- bad daughters

Understanding the socio-cultural symbolism of the practice of FGM/C without a ethnocentric gaze, would prove helpful in advocating for an alternative practice that holds the same cultural meaning, without eroding the social cohesion of the members of that culture. In Kenya, Alternative Rites of Passage(ARP) are becoming increasingly popular as an alternative to FGM/C. This process allows young girls to partake in a rite of passage to womanhood, without undergoing the FGM/C procedure. In these ceremonies and the instruction that precedes them, girls’ human rights (mainly to life, health, education, protection) and cultural rights (manifested in teachings and ritual elements that aim to mimic the cultural traditions of the community concerned) are intertwined in one social space.18

Parents/Guardians who allow the procedure to be performed on their daughters, do it out of concern for her well-being and to secure her future. Many do not fully understand the short and long-term consequences of the practice, and are open and willing to change when informed of the medical and psychological implications. It is unfair to label them as perpetrators of violence, as it risks alienating and offending them rather than convincing them to abandon the practice.Therefore, in calling for a ban or criminalization of the practice of FGM/C, let us not be dismissive of the socio-cultural function that this practice serves in the cultures where its been practiced. It is paramount for social actors to apply a non-stigmatizing and non-judgmental approach, to further encourage the incorporation of strategies that recognize women’s active role and agency in the re-invention and perpetuation of FGC when developing strategies to enhance the abandonment of FGC.

Sources

- 1. Clarke E, Richens Y. Female genital mutilation: an ‘old’problem with no place in a modern world. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2016 Oct;95(10):1193-5.

- 2. Female Genital Mutilation or Cutting Factsheet from the Office on Women’s Health (2018)

- 3. World Health Organization: Female Genital Mutilation (2020) https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation

- 4. World Health Organization: Female Genital Mutilation: Integrating the Prevention and the Management of the Health Complications Into the Curricula of Nursing and Midwifery: A Student’s Manual. Geneva, WHO, 2001, pp 25–27

- 5. Utz-Billing, I. and Kentenich, H., 2008. Female genital mutilation: an injury, physical and mental harm. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 29(4), pp.225-229.

- 6. M. O. Ofor and N. M. Ofole, “Female genital mutilation: the place of culture and the debilitating effects on the dignity of the female gender,” European Scientific Journal, vol. 11, pp. 112–121, 2015.

- 7. Behrendt, A. and Moritz, S., 2005. Posttraumatic stress disorder and memory problems after female genital mutilation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(5), pp.1000-1002.

- 8. Reisel, D. and Creighton, S.M., 2015. Long term health consequences of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM/C). Maturitas, 80(1), pp.48-51.

- 9. Brady, M., 1999. Female genital mutilation: complications and risk of HIV transmission. AIDS patient care and STDs, 13(12), pp.709-716.

- 10. Utz-Billing, I. and Kentenich, H., 2008. Female genital mutilation: an injury, physical and mental harm. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 29(4), pp.225-229.

- 11. Moges, A., 2009. What is behind the tradition of FGM/C. African Women Organization.

- 12. The Guardian: A ban on Male circumcision would be Antisemtic. How could it not be?https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/oct/11/ban-male-circumcision-antisemitic

- 13. WHO, UNAIDS, 2010. Neonatal and child male circumcision: A global review: http://www.circlist.com/considering/neonatal_child_MC_UNAIDS.pdf (Accessed Nov 5, 2020).

- 14. Esho, Tammary & Enzlin, Paul & Van Wolputte, Steven. (2011). The socio-cultural-symbolic nexus in the perpetuation of female genital cutting: a critical review of existing discourses. Afrika Focus. 24. 53-70. 10.21825/af.v24i2.4997.

- 15. Sakeah, E., Debpuur, C., Oduro, A.R. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with female genital mutilation among women of reproductive age in the Bawku municipality and Pusiga District of northern Ghana. BMC Women’s Health 18, 150 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0643-8

- 16. United States Department of State, Ghana: Report on Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) or Female Genital Cutting (FGC), 1 June 2001, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/46d57878c.html [accessed 8 November 2020].

- 17. Earp B. Female genital mutilation and male circumcision: toward an autonomy-based ethical framework. Medicolegal and Bioethics. 2015;5:89-104 https://doi.org/10.2147/MB.S63709

- 18. Lotte Hughes (2018) Alternative Rites of Passage: Faith, rights, and performance in FGM/C abandonment campaigns in Kenya, African Studies, 77:2, 274-292, DOI: 10.1080/00020184.2018.1452860